Guest post by E P Wohlfart

So dark is the night of midwinter

But behold, approaching Lucy

She comes, the Good One, to us with light

She comes with greetings of Christmas peace

She comes with candles in her crown

(Popular Swedish Saint Lucy’s Day song)

On the 13th of December, the night of Midwinter in the old Julian calendar, my native Sweden is entranced by a beautiful procession of young girls and boys in white cotton gowns. The girls carry candles, the boys wear white star-embellished cones on their heads, and heading the procession is a girl with a crown of candles in her hair, and a ribbon of flowing red around her waist.

She is Saint Lucy, and the entire first half of Advent is spent voting on the thousands of lucky young ladies who will be this year’s saintly representative in their locality. Like so many Swedish traditions, this one is born out of a mixture of foreign influence, a hint of genuine tradition, and a healthy dose of enthusiastic early 20th century effort.

The first half of Advent is also spent enjoying what is often held to be Saint Lucy’s eponymous pastry: the lussekatt. This sweet saffron bun is loved by all and eaten in enormous quantities. In reality, however, it has very little to do with the Sicilian martyr Saint Lucy and her modern light-bringing. Its older name is dövelskatt, from the word for Devil, and its purpose, amongst other things, has been to ward off evil.

This brings us back to Swedish Saint Lucy’s Day celebrations. Long before there was a Catholic saint associated with this day, there was an Indo-European belief that around Midwinter the limits between this living world and the next became blurred. Ghouls, ghosts, demons, and, originally, Pagan gods of the dead, slipped back and forth across the border. It was a dangerous time to be a mortal human. Traditions relating to this belief are found all across Europe. In Sweden, it came in the shape of the lussivaka, or the Lussi Wake. Because it was considered lethal to fall asleep on the Eve of Midwinter, people stayed awake through the night. They were driven to this from the fear of the Lussi Hag, or in some parts of Sweden: the Lussi Man. This entity was in charge of lussiferda, a dangerous host of chaotic spirits that rode through the air and harmed, killed, or cursed anyone in their way.

The lussekatt pastry was not only a sweet treat to break the long evening’s fast, it was a way of saving one’s soul from those evil spirits. In parts of Sweden in the 19th century, it was carried while travelling in the dark of Midwinter. If there was any sound of demons behind you, tradition has it, you should toss the bun over your shoulder and run. The devils will surely choose to take the bun, rather than your soul.

It is also believed that the lussekatt, which can be interpreted to mean Lucifer-cat, came from Germany or the Netherlands, where the Child Jesus handed out treats for children and Lucifer, in the shape of a cat, beat them. The bright yellow bun was said to scare the Lucifer-cat away, since he fears the light.

Some scholars have traced the sweet treat to cult breads from the Viking era, celebrating Freya and the cats that drew her chariot. Given that some scholars have linked female leaders of Midwinter spirit hosts, such as the Swedish Lussi Hag and the German Perchta, with Freya that is certainly an interesting thought. To ward off lussi-demons of your own, though, or just to celebrate the light-bringer Saint Lucy, just follow this simple recipe:

Lussekatter

Ingredients

50 g (1.8 oz) of fresh yeast, or enough dry yeast for 1 kg of flour

100 g (3.5 oz) of unsalted butter

0.5 litres (1 pint) of whole milk

250 g (8.8 oz) of quark (can be omitted if hard to find, just use more milk)

1 g (0.04 oz) of saffron

100 g (3.5 oz) of granulated sugar

0.5 teaspoons of salt

approximately 1 kg of white wheat flour

1 egg

raisins

Instructions

Melt the butter, add the milk and heat to body temperature. Transfer the liquid into a bowl and mix first with the yeast, if fresh, and then with the remaining ingredients, except for the egg and the raisins. The dough should be smooth and no longer stick vigorously to the bowl, but if it gets too dry it will be difficult to roll. Cover the dough and let it rise for 30 minutes. Divide your dough into 20 or so parts.

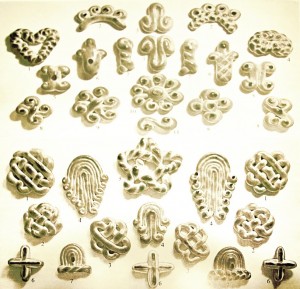

Look at a diagram for lussekatter to determine how many parts to divide each one into for your preferred bun. The classic julkuse requires no further division. Simply take your piece of dough and roll it into a strip at least the length of your hand. Start rolling up the edges, each in a different direction, until they meet and form a S-shape. Put your lussekatter on a baking sheet and heat your oven to 225°C (435°F) while they rest for another 20 minutes.

Whisk up your egg with a fork and brush the buns. Push raisins into all the little spirals. Finally, bake for 5-10 minutes. Enjoy with mulled wine, and if you hear ghouls behind you, just drop the bun and run.

Originally from Sweden, E P Wohlfart is an ancient historian currently living in France.