Does Christmas make you want to shout Bah Humbug? You are not alone. Nor is the much touted “War Against Christmas” anything new. Oliver Cromwell goes down as history’s biggest Grinch. The Lord Protector and his Puritan-led parliament literally stole Christmas in mid-17th century England.

A fervent Puritan, Cromwell was on a mission to cleanse his nation of what he perceived to be papist excess and decadence. He and his fellow Puritans regarded Christ’s Mass as an unwelcome revenant of Catholicism, “a popish festival with no biblical justification.” Nowhere in the Bible, they argued, were people asked to celebrate Christ’s nativity on December 25. Moreover, in Cromwell’s mind, the wild, hedonistic excesses associated with the Twelve Days of Christmas, stretching from Christmas Eve to Twelfth Night, undermined core Christian beliefs.

On November 19, 1644, Parliament resolved that Sunday was the “only standing holy day under the New Testament” and within a week they decided that no other holy day would be recognized. The new national liturgy issued on January 4, 1645, made no provision for Christmas and thus its abolition was legally achieved, although a parliamentary ordinance declaring Christmas celebrations a punishable offence was not passed until 1647.

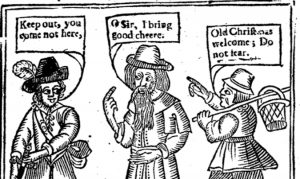

Traditionally the Twelve Days of Christmas was a time of feasting, merrymaking, drinking, mumming, gaming, and dancing. Special plays and masques were performed. It’s no accident that one of Shakespeare’s most popular comedies is named Twelfth Night after the festive date of its début performance.

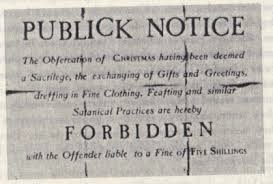

The Puritans viewed these festivities as wasteful vanities, an excuse for misrule, drunkenness, promiscuity, gluttony, and gambling. Under Puritan rule, all activities related to Christmas celebrations, including Anglican religious services, were banned and driven underground. In London, soldiers were ordered to seize special foods cooked in celebration of Christmas, such as roast goose. The day of Christ’s birth was no longer a holiday–people were expected to be seen at work and were questioned if they were not. The sacred significance of the day could only be legally observed with fasting and private prayer. Exchanging gifts, wearing fine clothes, feasting, and dancing were punished with a fine of five shillings.

The ban on Christmas endured after Cromwell’s death in 1558 and was only repealed with the Restoration of 1660. Likewise the Puritans of New England banned Christmas in Boston between the years 1659 and 1681.

In Restoration-era England, the Anglican Church resumed its traditional Christmas observances. However, hardline Protestants, such as the Presbyterian Kirk in Scotland, continued to discourage Christmas celebrations long after Cromwell’s demise.

Richard is a friend of mine, born in the 1960s in a remote village in the Scottish Highlands. In his tight-knit, kirk-attending community, he never celebrated Christmas. Instead the midwinter revels took place at Hogmanay, the Scottish New Year’s celebration, an unabashedly hedonistic celebration of dancing, drinking, parades, and festivals.

Hogmanay, like many folkways related to Christmas itself, may have its roots in ancient, pre-Christian Celtic or Norse midwinter celebrations.

“We drank like heathens,” Richard remembers fondly.

No doubt Cromwell is rolling over in his grave.

Source: Ronald Hutton, The Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain