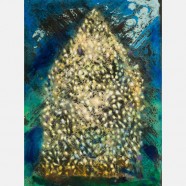

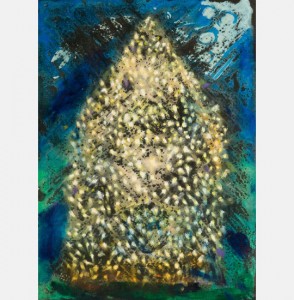

Elizabeth Erickson’s 2008 painting “Hildegard’s House of Light.”

Today marks the First Sunday of Advent and the first post of our Viriditas Interfaith Advent Calendar, “Journey into Light.”

Here in Northern England, I find myself plunging into the depths of midwinter darkness. It is in this womb of night and stillness that the Light is reborn. Through the ages and across cultures, world faith traditions have marked this sacred passage through the darkness, as our guest bloggers shall explore in the coming days of Advent.

In Christian tradition, Advent is a period of expectant waiting, of anticipating the birth of Christ. The word Advent comes from the Latin adventus, which means “coming.” This First Sunday of Advent marks the beginning of the Western Christian liturgical year.

The Advent wreath and Advent calendar are relatively recent innovations. Christmas and Advent celebrations have gone through many permutations throughout history, as our guest bloggers will reveal, from boisterous celebrations with mummers and feasting to Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan backlash in which he outlawed Christmas because he believed the feast was far too pagan.

Back in Hildegard von Bingen’s day, in the 12th century, Advent was a season of fasting and penitence in preparation for the Twelve Days of Christmas, which begin on Christmas Eve and end on January 6, the Feast of the Epiphany.

The season would have been especially numinous for Hildegard as a child anchorite at the remote Benedictine monastery of Disibodenberg. Imagine the enduring the depths of midwinter without central heating or electric lights, in an age when even religious people believed that there were demons lurking in the shadows. This would have pitched Hildegard into the deep drama of the season—the rebirth of the Light out of teeming darkness.

One German seasonal tradition that young Hildegard might have treasured was the Barbara Zweig, or the Barbara Branch. This was a branch cut from a fruit bearing tree on the Feast of Saint Barbara, December 4. Kept in a vase of water in a warm and sunlit corner, it would bloom on Christmas Day.

There were other, more atavistic traditions associated with the season. In Northern Europe, long before the Christian era, the Twelve Nights of Yule were held in awe—time out of time when fate hung suspended, when secrets were revealed and fortunes could be reversed, when the most powerful magic was afoot. Well into the Christian era, people believed that the ghostly Wild Hunt still roared across the midwinter skies along with the gales and storm winds.

I experienced these traditions first hand when I lived in Germany. In the Bavarian town of Kirchseeon, just east of Munich, mummers in hand-carved wooden masks perform the “Perchtenlauf,” a wild torchlit procession through the winter forest to awaken the dormant nature spirits and call back the dwindling sun. I’ll discuss these folkways in greater depth in another post.

Now we return to young Hildegard, the child anchorite at Disibodenberg Monastery.

Here is an excerpt from Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen:

After Vespers, I went to see if our Barbara Branch still had enough water. Though the buds had once seemed to swell, it now felt like a dead twig I could snap between my fingers. The forest would not stop haunting me. How the wild places called out to me in the face of Jutta’s direst warnings. Again and again she told me that I must dread everything dark and untamed.

Demons ruled the nocturnal hours, she insisted. On stormy nights, outside our anchorage walls, trees writhed, tossing their branches against the moon-drenched sky. As I lay in my narrow bed, my ears rang with the shrieking wind, the cries of owls and wolves in search of prey.

Little did it matter that Christmas was fast approaching. For centuries before the Irish missionaries brought the faith of Christ to this land, before Carolus Magnus toppled the Irminsul, the idolatrous pillar of the heathens, my ancestors had held the Rauhnaechte, the Twelve Nights of Yuletide, in awe—time out of time when fate hung suspended, when secrets were revealed and fortunes could be reversed. This I knew from Walburga’s tales. The servants and peasant folk back home had muttered stories of the Old Ones roaring across the midwinter skies: the Wild Hunter of a thousand names in pursuit of his White Lady with her streaming hair and starry distaff, the whirlwind before the storm.

Leaving Jutta to her dreams, I crept out of bed and stole into the courtyard where I pranced barefoot in the swirling snowflakes like the mummers who came to Bermersheim every Yuletide in their fearsome wooden masks to frighten away harmful spirits.

A gale howled overhead, and the cold stung my soles, sending me spinning as the Wild Hunt of Walburga’s nursery stories raged overhead, that endless stream of unbanished gods and the souls of the unchristened dead. Anyone who dared venture out on a night such as this risked being swept along in that unearthly train.

But did I cross myself and flee inside to safety? No, I raised my face to the clouds racing across the full moon and I begged those invisible riders to take me with them.

Clouds shrouded the moon. Everything went black. I plummeted, down and down, as if there would be no end to my falling. De profundis clamavi ad te. Gazing up from the depths, I saw a circle of sky, now emptied of moon and stars. Had I been cast into hell for my sin? From out of that murk came a white cloud bursting with a light that was alive, pulsing and growing until it blazed like a thousand suns.

In that gleaming I saw a maiden shine in such splendor that I could hardly look at her but only catch glances like fragments from a dream. Her mantle, whiter than snow, glittered like a heavenful of stars. In her right hand she cradled the sun and moon. On her breast, covering her heart, was an ivory tablet and upon that tablet I saw a man the color of sapphire. A chorus rose like birdsong on an April dawn—all of creation calling this maiden Lady. The maiden’s own voice rose above it, as achingly beautiful as Jutta’s singing.

I bore you from the womb before the morning star.

I didn’t know whether the maiden was speaking to me, lost and wretched, or to the sapphire man in her breast. My vision of the Lady was lost but her voice lingered. You are here for a purpose though you don’t understand it yet.

Barefoot and mother naked, I found myself within a greening garden so beautiful, it made me cry out. Each blade of grass and newly unfurled spring leaf shimmered in the sun. Every bush and tree was frothy with blossom and heavy with fruit at the same time. In the midst of that glory, the Tree of Life with its jeweled apples winked at me, and yet I saw no serpent. The Lady’s voice whispered: See the eternal paradise that has never fallen.

I saw a great wheel with the all-embracing arms of God at its circumference, the Lady at its heart. Everything she touched greened and bloomed.

Pealing bells wrenched me back into this world. The monks were ringing in Christmas morning. I lay on my pallet, the blankets piled over me, my legs swaddled in damp cloth. Above me hovered a maiden with glowing blue eyes. Her veil had slipped and the sun shone through her halo of cropped auburn curls. Whispering my name, Jutta held out a blossoming apple branch, each pink and white flower scented of the Eden I had glimpsed.

lovely!

Thank you, Kirsten!

Are you familiar with Rudolph Steiners winter spiral?

No, I’m not!

Enjoyed reading Mary, great post