In popular imagination, the figure of a witch is accompanied by her familiar, a black cat. Is there any historical authenticity behind this cliché?

Our ancestors in the 16th and 17th centuries believed that magic was real. Not only the poor and ignorant believed in witchcraft and the spirit world—rich and educated people believed in spellcraft just as strongly. Cunning folk were men and women who used charms and herbal cures to heal, foretell the future, and find the location of stolen property. What they did was illegal—sorcery was a hanging offence—but few were arrested. The need for the services they provided was too great. Doctors were so expensive that only the very rich could afford them and the “physick” of this era involved bleeding patients with lancets and using dangerous medicines such as mercury—your local village healer with her herbal charms was far less likely to kill you.

Those who used their magic for good were called cunning folk or charmers or blessers or wisemen and wisewomen. Those who were perceived by others as using their magic to curse and harm were called witches. But here it gets complicated. A cunning woman who performs a spell to discover the location of stolen goods would say that she is working for good. However, the person who claims to have been falsely accused of harbouring those stolen goods could turn around and accuse her of sorcery and slander. Ultimately the difference between cunning folk and witches lay in the eye of the beholder.

While witch-hunters were obsessed with extracting “evidence” of a pact between the accused witch and the devil, there’s little if any substantive proof of diabolical worship in Britain in this period. It seemed the black mass was a Continental European concept first popularised in Britain by King James I’ polemic, Daemonologie, a witch-hunter’s handbook and required reading for his magistrates.

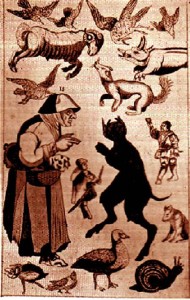

In traditional British folk magic, it was not the devil, but the familiar spirit who took centre stage. The familiar was the cunning person’s otherworldly spirit helper who could shapeshift between human and animal form. Elizabeth Southerns, aka Old Demdike, was a cunning woman of long standing repute, arrested on witchcraft charges in the 1612 Pendle witch hunt in Lancashire, England. When interrogated by her magistrate, she made no attempt to conceal her craft. In fact she described in rich detail how her familiar spirit, Tibb, first appeared to her when she was walking past a quarry at twilight. Assuming the guise of a beautiful, golden-haired young man, his coat half black, half brown, he promised to teach her all she needed to know about the ways of magic. When not in human form, he could appear to her as a brown dog or a hare. Her partnership with Tibb would span decades.

Mother Demdike was so forthcoming about her familiar because without one, she, as a cunning woman, would be a fraud. In traditional English folk magic, it seemed that no cunning man or cunning woman could work magic without the aid of their familiar spirit—they needed this otherworldly ally to make things happen.

Black cats were not the most popular guise for a familiar to take. In fact, familiars were more likely to appear as dogs. In the Salem witch trials of 1692, two canines were put to death as suspected witch familiars.

But the familiar was just as likely to assume human form, generally the opposite gender of their human partner—cunning men usually had female spirits while cunning women usually had male spirits.

Was there a connection between the familiar spirits and the Fairy Faith, the lingering belief in fey folk and elves? Popular belief in fairies in the Early Modern period is well documented. In his 1677 book, The Displaying of Supposed Witchcraft, Lancashire author John Webster mentions a local cunning man who claimed that his familiar spirit was none other than the Queen of Elfhame herself. In 1576, Scottish cunning woman Bessie Dunlop, executed for witchcraft and sorcery at the Edinburgh Assizes, stated that her familiar spirit had been sent to her by the Queen of Elfhame. For more background on this subject, I highly recommend Emma Wilby’s scholarly study, Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits, and Keith Thomas’s social history, Religion and the Decline of Magic.

It’s always confused me the cunning folk and the witch. I have read also that if the cunning folk failed at her say healing a sick child or animal that they would then accuse her of being a malicious witch. And that some folk maybe widows would try make ends meet by selling charms,talismans and offer various gifts such as getting in touch with dead sprits.

What is also interesting in a story I heard today is that often a village would hide their cunning folk from church goers, protecting her/him.